|

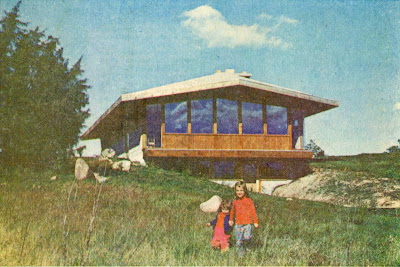

| Entry elevation of Moraine End residence. |

I was sorting through stacked storage boxes recently and ran across old books, newspaper clippings and other odds and ends I had saved about architecture and architects. Among them were items by and about LaVerne Lantz (1929-1998), an early architectural mentor of mine. The newspapers were brown and ragged. I thought it was time to commit some of these things to the www so they can preserved in a (hopefully) longer-lasting electronic format.

|

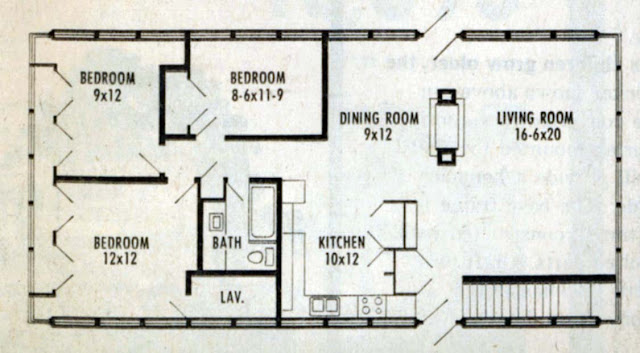

| Floor plans for the first Lantz residence on Moraine End. |

Every architect has mentors early in life who are important to the development of their design philosophy and professional practice. In fact, to become a registered architect in the United States, a mentoring/apprenticeship experience is required in addition to formal education and licensing exams. The biggest personal influence on my life as an architect was LaVerne Lantz. He and his wife Molly became my "second family" when I was sixteen. They shared generously their home, time, books, ideas, and encouragement.

|

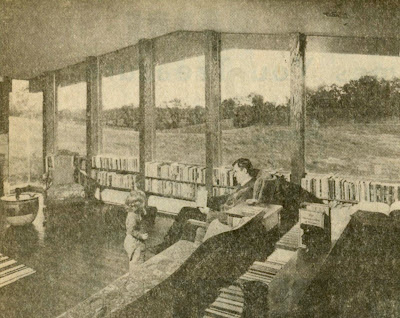

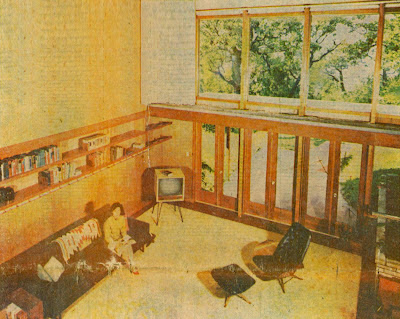

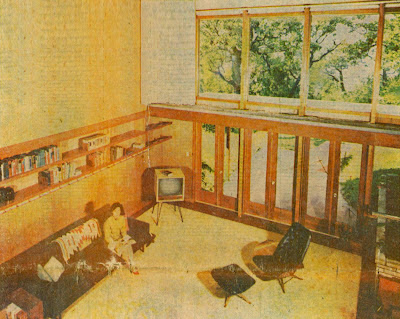

| Living room with Molly Lantz, seated, and Lake Nagawicka in the distance. |

LaVerne Lantz built a respected practice of architectural design primarily in the forested hills of southeastern Wisconsin. His work followed the principles of Frank Lloyd Wright with rigorous and clear discipline -- particularly Wright's Usonian period of the nineteen forties and fifties.

In

The Well Designed Home, a promotional piece he wrote for prospective clients, LaVerne Lantz expressed the philosophy behind his architecture:

- ... the most comfortable home is the one that is close to nature.

- All houses have depth, but most conventional dwellings have a confined sense of depth because "rooms", rather than space, dominate. If there is not a feeling of space, the design is a failure.

- A basement is usually a dingy, confining, costly hole-in-the-ground with dampness and odor problems. To be at all justified, a basement should be opened out on a sloping lot, or partially raised out of the ground on a flat lot.

- ...planning for pasive solar heat has been part of good design long before the current popular interest. With the correct roof overhangs and glass combinations, the sun can be a controlled source of heat throughout much of the house.

|

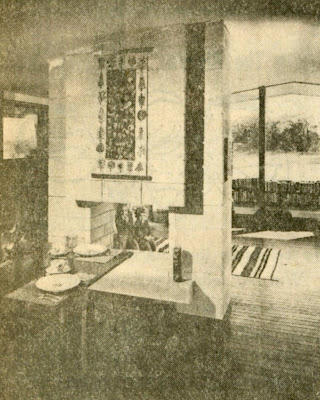

| Living room fireplace with guest balcony above. |

Lantz often expressed the importance of keeping architecture close to nature and deriving form from natural materials.

- Kept close to its natural color, wood is a very warm and comfortable material. Its grain is what makes it beautiful and therefore should be emphasized.

- Stone... is "of" the earth. What we CAN do with stone is almost limitless, but what we SHOULD do with it is part of good design.... It should not be made into spindly posts or cantilevered more than a very short distance.

- The easiest colors to live with over a long period of time are the warm colors of nature: yellows, oranges, browns, tans, reds or combinations of these.

|

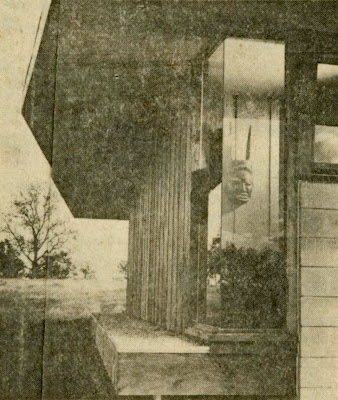

| A planter emphasizes the indoor/outdoor connection. |

Lantz also had little tolerance for typical subdivisions or mass-produced housing.

- Conventional "styles", almost endless in variety and very loosely mimicking the dwellings of the past, are nothing more than facades slapped on the typical box to make the customer think they are getting something different.

- Homeowners and professional interior decorators attempt to make the typical house livable by periodially changing color schemes, window treatment, and furnishings. The well designed home, on the other hand, is totally designed inside and out, and the decorator...can do nothing to enhance it.

|

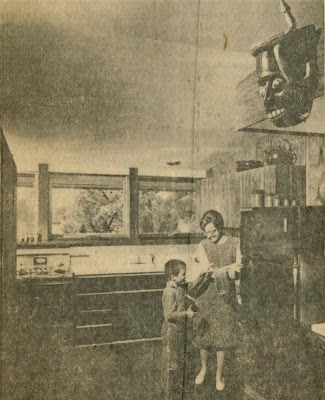

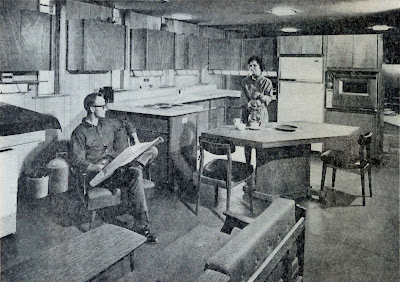

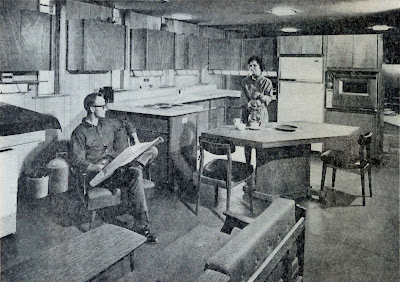

| Family room/kitchen with LaVerne and Molly Lantz. |

LaVerne Lantz had a deep appreciation and natural talent for organic architecture. One of my favorite examples of his work (and the first I ever experienced) is the home he and Molly built on Moraine End in Delafield, Wisconsin.

The Milwaukee Journal featured his work in several articles by Oliver Witte. The house on Moraine End was the subject of one of those articles. The faded pictures reproduced here are from the

Home Section, September 5, 1965. Witte wrote that the space in this house "seems to flow from one room to another and from the interior to the out of doors." That perception is fully consistent with the philosophy of midcentury architects and designers who followed the precepts of Frank Lloyd Wright. LaVerne Lantz deserves recognition amongst the panolply of mid-century modernists that nurtured that philosphy and kept it alive.

Journal photos: John Ahlhauser